OpioidSettlementGuides.com is live!

Vital Strategies and I jointly produced this resource, launched December 2024, to serve as the definitive encyclopedia all U.S. states’ opioid settlement spending processes. It expands upon and replaces the 2023 Community Guides that used to live on this page.

Our state-specific Guides include confirmation and exclusive detail from states’ AGs, departments of health, and other decision-makers, so many of whom were generous enough to work directly with us on getting this resource right. Each of the 50 + D.C. states’ guides on OpioidSettlementGuides.com answers key questions for each share of a state’s settlement funds:

Where exactly do my state’s opioid settlement funds live?

Who ultimately decides how my state’s opioid settlement funds are spent: advisory council members, state legislatures, health departments, or local government officials?

What must my state’s opioid settlements be spent on, and what processes must be followed as they are spent?

Has my state established an opioid settlement advisory body? And is that body required to include member(s) with lived and/or living experience?

Can I provide input on spending? Are my state’s decisionmakers required to hear the public’s input on opioid settlement spend?

Are any of my state’s opioid settlements at risk of being used to supplant existing health resources?

Where should I go for updates, and what are key opioid settlement spending resources I should know about in my state?

Thank you to The Associated Press for your coverage of our launch.

See Geoff Mulvihill’s “How should the opioid settlements be spent? Those hit hardest often don’t have a say”

“Christine Minhee of Opioid Settlement Tracker and Vital Strategies, a public health organization, released a state-by-state guide on Monday outlining how government funding decisions are being made. The guide aims to help advocates know where to raise their voices.

Using that information and other data, Minhee, who has tallied just under $50 billion in settlements excluding one with OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma that the Supreme Court rejected, found advisory groups help determine spending of about half of it. But they have decision-making authority over less than one-fifth of it.

Less than $1 in $7 is overseen by boards that reserve at least one seat for someone who is using or has used drugs, though some places where it’s not required may have such members anyway.”

“How should the opioid settlements be spent? Those hit hardest often don’t have a say” (December 9, 2024)

OTHER ITEMS ON THIS PAGE

This page documents states’ plans for their opioid settlement winnings.

For the birds-eye view of opioid settlements reached thus far, visit the Global Settlement Tracker (quick jump: States’ Opioid Settlement Statuses).

About OpioidSettlementGuides.com

How OpioidSettlementGuides.com (co-produced by me and Vital Strategies) relates to OpioidSettlementTracker.com (still independently run by Christine), plus how it improves upon my and Vital Strategies’ 2023 Guide for Community Advocates (now archived).

Opioid Settlement Spending Webinars and Explainers

A collection of my mini-lectures about the opioid settlement spending landscape.

Settlement Spending FAQs

Will states be misspending their opioid settlement dollars?*

Why have states’ opioid spending plans taken the form of contracts and legislation?*

“How Are Opioid Settlement Funds Being Spent So Far?” (Health Affairs Forefront)

*Excerpted from my greater Opioid Settlement FAQs page.

There is much drama re: what states and localities have spent their monies on thus far. OpioidSettlementGuides.com is a resource that reliably describes what we can expect from now until 2035 (when states' settlement payments end), and how we can run that race to save lives while spending this historic transfusion of funds with a marathon mindset.

This website expands upon and replaces the “Guides for Community Advocates” section that used to live on this page. (All other pages and tracking projects hosted on this site will continue as normal.)

OUR 2023 GUIDES = A BUNCH OF .PDFS HOSTED HERE

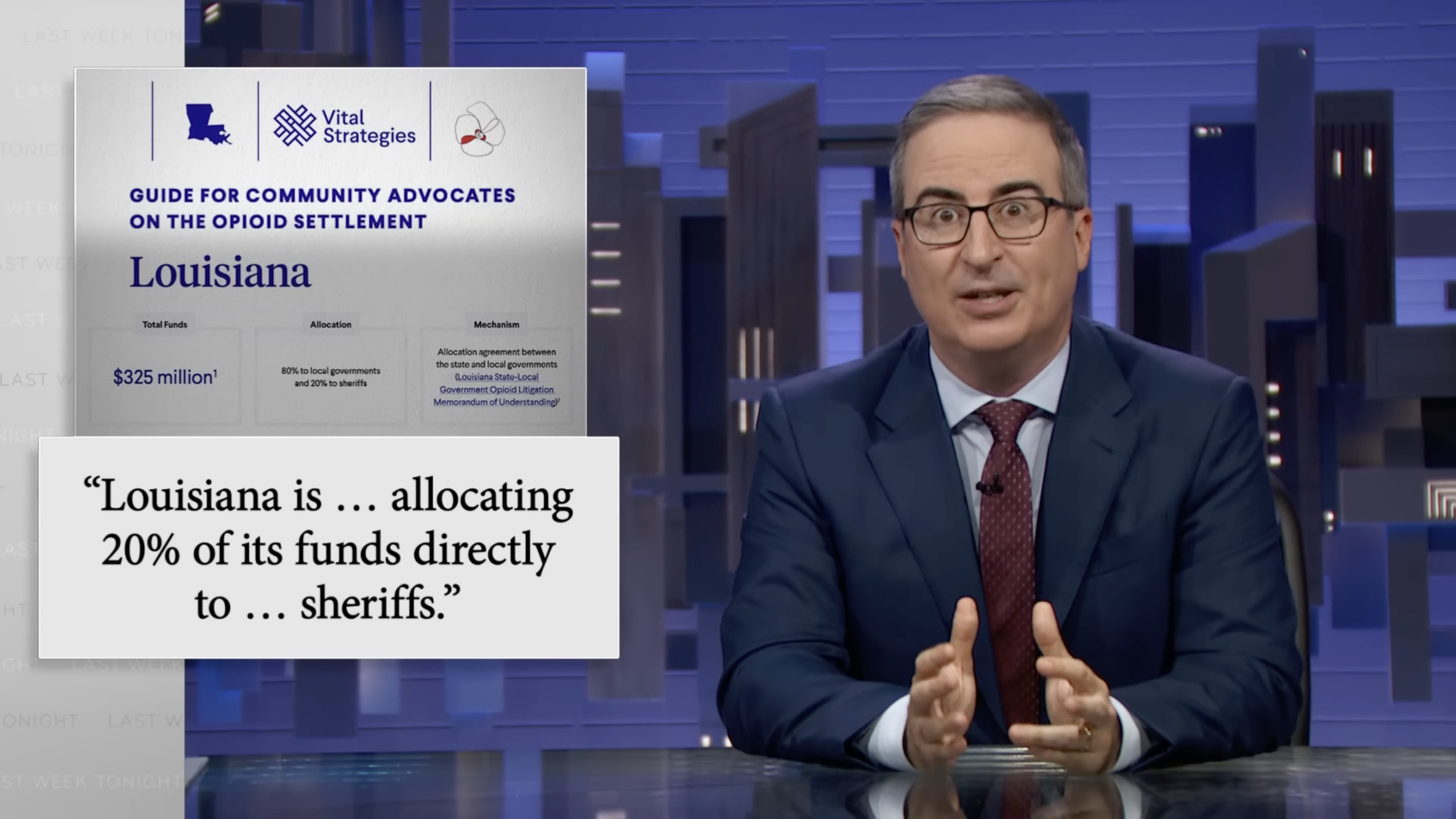

Vital Strategies and I launched our original set of Guides (“Guides for Community Advocates on the Opioid Settlement”) in June 2023 to equip community advocates with expert-level analyses of each state’s unique opioid settlement spending approach. These were the Guides featured in John Oliver:

Opioid Settlements: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (aired Sunday, May 12, 2024; available on YouTube and HBO Max)

OUR 2024 GUIDES = A BRAND-NEW, STANDALONE WEBSITE

OpioidSettlementGuides.com is our 2024 update to our 2023 Guides for Community Advocates. We launched this website on December 9, 2024, alongside coverage featuring our launch and data from The Associated Press:

See Geoff Mulvihill’s “How should the opioid settlements be spent? Those hit hardest often don’t have a say”

What’s new in the 2024 update?

States and localities have continued to refine their spending goals and processes as they spend their first few settlement payments. The guides have all received a comprehensive update and contain new and essential information, including recently enacted legislation, changes to decision-making processes, and recent input opportunities. Many of the guides also reflect important insights and clarifications as reported by the states themselves. Read more about our methodology here.

OPIOID SETTLEMENT SPENDING WEBINARS & EXPLAINERS

A collection of my mini-lectures about the opioid settlement spending landscape.

“With Big Tobacco’s cautionary tale shadowing these debates, the issue of accountability looms. Who ensures that grantees spend their money appropriately? What sanctions will befall those who color outside the lines of their grants?

So far, the answers remain to be seen. Christine Minhee, a lawyer who runs the Opioid Settlement Tracker, which analyzes state approaches to spending the funds, noted that on that question, the voluminous legal agreements could be opaque.

‘But between the lines, the settlement agreements themselves imply that the political process, rather than the courts, will bear the actual enforcement burden,’ she said. ‘This means that the task of enforcing the spirit of the agreement — making sure that settlements are spent in ways that maximize lives saved — is left to the rest of us.’”

— "Opioid Settlement Money Is Being Spent on Police Cars and Overtime" (The New York Times)

SETTLEMENT SPENDING FAQs

A bit o’ background as to why opioid settlement spending plans are important at all.

(FAQs below are excerpted from my greater Opioid Settlement FAQs tab.)

How do states’ plans relate to the $26 billion global settlement offer made by McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and Johnson & Johnson?

How the $26 billion “national” or “global” settlement relates to other opioid settlements: Though often described as “national” or “global,” that widely reported $26 billion settlement — which resolves opioid crisis-related lawsuits between both sets of government plaintiffs (46 states’ Attorneys General and their participating localities) and just four opioid litigation defendants (“big three” distributors McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal Health and manufacturer Johnson & Johnson) — is not the whole egg. It’s at best the yolk of all opioid settlements expected by governments involved in opioid litigation nationwide, with the rest coming from resolutions with those other defendants not included in the $26 billion deal (e.g., Purdue, Mallinckrodt, McKinsey, and all of the pharmacies).

How the plans listed above relate to the $26 billion settlement, and why its requirements are important for opioid settlement spending watchdogs to study: Given that it makes up the biggest chunk of all anticipated opioid settlements, states and localities have been paying the heaviest attention to its requirements. The most notable among them — and the most valuable for watchdogs to know! — is that all states are required to spend at least 70% of their slice of that $26 billion pie on future opioid remediation…

Will states be misspending their opioid settlement dollars?

Probably not as poorly as they misspent their big tobacco dollars, given that there are clear contractual protections against that outcome. The juiciest among them:

All states are required to spend at least 70% of their share of that $26 billion settlement on future opioid remediation.

An explanation, with receipts (citations):

This 70% “future opioid remediation” threshold requirement — one that all participating states must meet — is baked into the language of the $26 billion settlement agreements: “Any State-Subdivision Agreement … shall be applied only if it requires: (a) that all amounts be used for Opioid Remediation, except as allowed by Section V.B.2, and (b) that at least seventy percent (70%) of amounts be used solely for future Opioid Remediation.” Section V.B.1. Section V.B.2 reiterates this threshold for allocation statutes, while Section V.E.2 provides that “[i]n the absence of a State-Subdivision Agreement, Allocation Statute, or Statutory Trust that addresses distribution, the Abatement Accounts Fund will be used solely for future Opioid Remediation.”

Combined with the way the agreements define Opioid Remediation, and with a little bit of math, this 70% threshold yields two other requirements incumbent upon all participating states:

A maximum of 15% of funds may be spent on opioid crisis-related reimbursement and administrative expenses. Section V.B.1 states that “[i]n no event may less than eighty-five percent (85%) of the Settling Distributors’ maximum amount of payments … be spent on Opioid Remediation,” which Section I.SS defines to include both future Opioid Remediation expenses (the explicitly prospective programming that’ll explicitly go towards abating future overdose crisis harms) and reimbursement and administrative expenses. Subtracting the 70% restricted to future Opioid Remediation, that leaves 15% for reimbursement and administrative expenses.

Non-Opioid Remediation expenses — i.e. roads, gubernatorial helicopters, and the other stuff of big tobacco spending retrospective-supplied nightmares — are capped at 15%. To state it as simply as I can, and to dip into some normative verbiage here: Only 15% of participating states’ funds may be spent on the bad stuff. And if settlement funds are spent on non-Opioid Remediation expenses, the settlement documents’ only reporting requirements attach (see Section V.B.2), which is to say nothing of the many optionally self-imposed expenditure reporting requirements I’ve seen in states’ plans (Arizona’s toothy reporting requirements come to mind here). Given that I’ve devoted my legal career to warning folks about the use of opioid settlement misspending. I find this provision heartening!

Therefore, the default allocation framework described in those $26 billion settlement documents — one that’d divvy up a state’s anticipated payout by giving 15% to the state, 15% to its subdivisions (cities and counties), and 70% to an “Abatement Accounts Fund” (the control over which might also rest with the state, depending on the state) — is just one way to satisfy that 70% future Opioid Remediation threshold.

But if you must know: Most states have wiggled away from the settlement agreements’ default allocation suggestions (that 15%-15%-70% thing). This is normal and predictable; each state must maximize lives saved within what is feasible within their jurisdictional (political) “set and settings” (however dystopic the Tim Leary reference in this context might be). As long as states meet the abatement-related thresholds described above, they can allocate their funds between the state government, local governments, and statutory trusts (if any) however they’d like… provided that the plan is articulated by one of three formats and adopts the settlement agreements’ greater requirements. From most commonly seen to least:

State-Subdivision Agreement — e.g., North Carolina’s MOA — “An agreement that a Settling State reaches with the Subdivisions in that State regarding the allocation, distribution, and/or use of funds allocated to that State and to its Subdivisions. A State-Subdivision Agreement shall be effective if approved pursuant to the provisions of Exhibit O or if adopted by statute. Preexisting agreements … shall qualify” (Distributor pg. 10).

Statutory Trust — e.g., Massachusetts’ Opioid Recovery and Remediation Trust Fund — “A trust fund established by state law to receive funds allocated to a Settling State’s Abatement Accounts Fund and restrict any expenditures made using funds from such Settling State’s Abatement Accounts Fund to Opioid Remediation” (Distributor pg. 11).

Allocation Statute — e.g., Indiana’s HB 1193 — “A state law that governs allocation, distribution, and/or use of some or all of the Settlement Fund amounts allocated to that State and/or its Subdivisions. In addition to modifying the allocation set forth in Section V.D.2, an Allocation Statute may, without limitation, contain a Statutory Trust, further restrict expenditures of funds, form an advisory committee, establish oversight and reporting requirements, or address other default provisions and other matters related to the funds” (Distributor pg. 1).

Are the risks of settlement misspending real?

Yes. Examples abound. Recently, New York’s Governor Cuomo used his state’s McKinsey settlement winnings to “supplant state aid rather than to supplement” the state’s overdose crisis prevention efforts, prompting state legislators to urge the passage of legislation that’d “ensure an ironclad, incremental lockbox for future settlement funds.” But the most laugh-cry example comes from now-Senator Joe Manchin; back when he was governor of West Virginia in 2007, he tried using his state’s Purdue settlement winnings to buy himself a personal helicopter.

As explained by Judge Polster himself: “The problem is that in a number of States any money that is, that a state attorney general obtains, either by victory in court, litigated judgment, or settlement, goes into the general fund. And the men and women who control what happens in the general fund are the elected state representatives and senators. That’s what they do. And that’s what happened in the tobacco litigation. Over $200 billion, far more than 90 percent of that was used for public purposes totally unrelated to tobacco smoking, lung cancer, whatever. And I believe that’s why we have all these counties and cities that filed separate lawsuits, to make sure that doesn’t happen again. ... [Any settlement] has to address the problem of putting money into the state general funds or else it isn’t going to fly.”

Why have states’ opioid spending plans taken the form of contracts and legislation?

As suggested by experts in Opioid Litigation Proceeds: Cautionary Tales From The Tobacco Settlement: “[R]evenue laws vary from state to state as do the specific language in settlement agreements related to the direction of money to general or restricted funds, yet legislation may be an effective measure to ensure funds are used toward responding to the crisis.” This is why we should generally be happy to see so many statutory trusts and allocation statutes boppin’ about in the spreadsheet above.

Additionally, contracts between the state and local governments have emerged as a vibrant, creative, and politically expedient (e.g., legislature-avoiding) way of articulating spending goals. Bloomberg Law correctly notes that settlement agreements between plaintiffs and defendants (i.e., from outside parties) can rarely dictate intrastate political processes. (“Some state attorneys general don’t have the power to allocate funds that belong to the legislature … . While a master settlement is a contract between parties, … it can’t change a state’s power structure.”) However, contractual agreements between intrastate government plaintiffs — e.g., the memoranda of understanding, state-subdivision agreements, intrastate allocation agreements between state and local governments — are effectively agreements to do so beforehand that manage to avoid offending constitutional separation of powers considerations.