Please note:

As of February 1, 2024, this investigation into states’ public reporting promises has been archived and replaced by my timelier investigation into the “fruits” of those initial transparency commitments.

All subsequent updates to states’ public reporting plans will be tracked not on this page, but through the Expenditure Report Tracker.

This page details reporting requirements under the biggest opioid settlement agreements and states’ promises to publicly report more than the bare minimum.

There are two other large, important spreadsheets on this site: States’ Opioid Settlement Statuses and States’ Opioid Settlement Allocation Plans.

States’ Initial Promises to Publicly Report Their Opioid Settlement Expenditures

This 51-state survey of states’ commitments to publicly report their opioid settlement spend was launched in collaboration with KFF Health News’ coverage on opioid settlement transparency and Transparency Map below. OpioidSettlementTracker.com has independently continued this investigation since April 2023.

The “initial” of my analysis’s title — States’ Initial Promises to Publicly Report Their Opioid Settlement Spend — reflects my hope that state governments will add to their commitments to publicly report their opioid settlement expenditures.

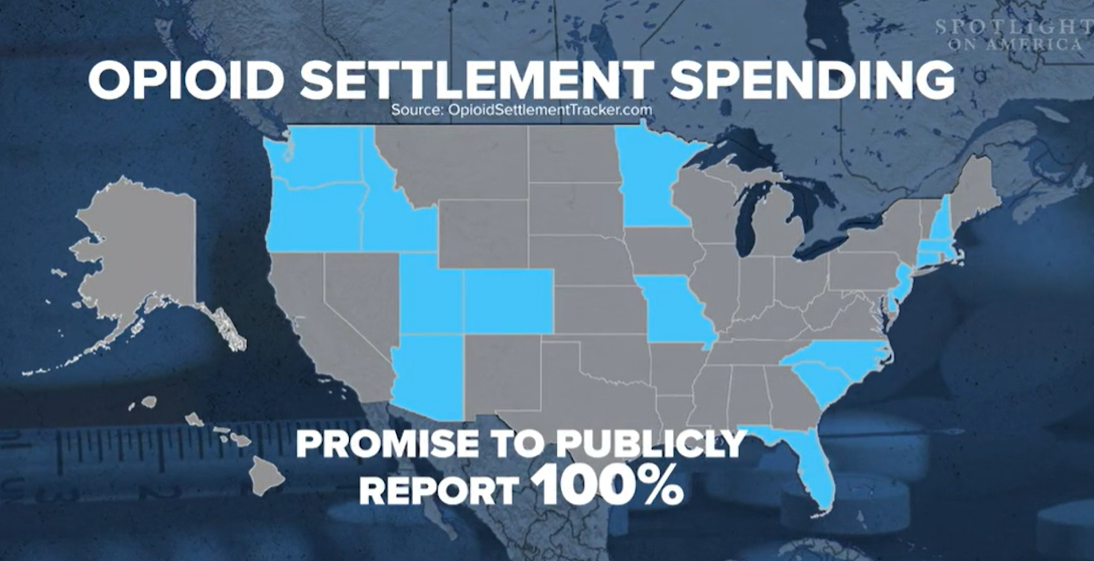

Opioid Settlement Transparency Map

In creating this map, KFF Health News used data from all three of the spreadsheets on this site: States’ Initial Promises to Publicly Report Their Opioid Settlement Spend (below), States’ Opioid Settlement Statuses, and States’ Opioid Settlement Allocation Plans.

“MOST SETTLEMENT AGREEMENTS DO NOT REQUIRE PUBLIC REPORTING OF OPIOID REMEDIATION EXPENDITURES”

Yes, it’s true. The Global Settlement Tracker’s reported sum of settlements between opioid corporations, states, and localities has reached $54.45 billion… and counting. The grand majority of this sum remains unattached to explicit requirements to publicly report opioid remediation-related expenditures.

Public Reporting Q&A

KFF Health News senior correspondent Aneri Pattani and I sat down for a Q&A to discuss the motivations behind this analysis. It doubles as a narrative explainer of our otherwise legalesey opioid settlement public reporting problem.

For frequently asked questions related to the opioid litigation and settlements as a whole, visit my greater Opioid Settlement FAQs tab.

“Your analysis shows that many states have some type of intra-state reporting requirement, but not as many have public reporting requirements. Why do you think that is?” →

“What could be done to improve public transparency on how this money is used?” →

“Would it be a big bureaucratic or administrative lift for states to require more public reporting?” →

“How do you hope this analysis will be used?” →

STATES' INITIAL PROMISES TO PUBLICLY REPORT THEIR OPIOID SETTLEMENT EXPENDITURES

As of January 31, 2024…

18 STATES HAVE REPORTED OR WILL REPORT 100% OF THEIR OPIOID SETTLEMENT SPEND TO THE PUBLIC

6 STATES HAVE JOINED THE 100% PUBLIC REPORTING FOLD SINCE THIS INVESTIGATION BEGAN IN 2023

As featured on ABC, NBC, etc. Initial research was completed in collaboration with KFF Health News in March 2023 and published alongside related coverage. OpioidSettlementTracker.com has independently continued this investigation since April 2023.

Below is my 51-state survey of states’ initial promises to publicly report their opioid settlement expenditures, launched March 2023 in collaboration with Kaiser Health News’ coverage on opioid settlement transparency and run independently by me since April. These promises derive from states’ planning documents for settlements with opioid distributors McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal Health and drugmaker Johnson & Johnson, which represent $26 of the $50 billion+ opioid settlement dollars on the table (and counting). My and KFF Health News’ complete methodology, including a note on applicability to other settlements, is below.

I have hope that if we merely knew how well our 100% reporting states were doing against the rest, the America of it all would kick in and our underpromising jurisdictions would strive to compete. At the end of March 2023, only twelve states had promised to publicly report 100% of their expenditures. Since April 2023, four states — Connecticut, Florida, North Carolina, and Washington — have joined the 100% public reporting fold.

From Spotlight on America’s “Lack of transparency concerns over billions in opioid settlement money distributions,” as featured on ABC, NBC, etc.

Shockingly, most* opioid settlement agreements do not require states and localities to report their opioid remediation expenditures to the public. The full breakdown of states’ bare-minimum public reporting commitments under the major opioid settlement agreements is below, and a narrative, Q&A version of the legalese is here.

But an optimistic curiosity ultimately drove this analysis. The operative word in its clunky title is “initial,” and the explicit goal of this project is for this count of public reporting promises to be rendered outdated by the states themselves:

Given that states’ and localities’ winnings wouldn’t have been possible without hundreds of thousands of individual lives lost, basic justice requires decision-makers to speak opioid settlement expenditures into the mic...

…both loudly and clearly enough for the people at the back of the room to hear.

18 states have explicitly promised to publicly report — or have actually publicly reported — 100% of their Distributor and Janssen settlement expenditures:

Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut (new!), Delaware, Florida (new!), Idaho, Indiana (new!), Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Carolina (new!), Oregon, South Carolina, South Dakota (new!), Utah, Washington (new!)

12 states have yet to commit to publicly reporting anything at all:

Alabama, Alaska, Hawaii, Illinois, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas

20 states + D.C. have promised to publicly report only a portion of their expenditures.

Last updated January 31, 2024. Please note: As of February 1, 2024, this investigation into states’ public reporting promises has been archived and replaced by my timelier investigation into the “fruits” of those initial transparency commitments. All subsequent updates to states’ public reporting plans will be tracked not on this page, but through the Expenditure Report Tracker.

“No explicit public reporting promises found, so default is presumed.” When you see this language, know that the “default” to presume would be the national settlement agreements’ bare-minimum mandate that only non-opioid remediation spending — a mere 15% — be eventually reported to the public. Breakdown of default reporting requirements here.

Yellow-highlighted cells represent areas where hope is on the move, so to speak. Stay tuned.

OpioidSettlementTracker.com has independently continued this investigation since April 2023. Initial research was completed in collaboration with KFF Health News and published alongside an article exposing issues arising from a lack of transparency on these funds. KFF’s Aneri Pattani, Colleen DeGuzman, and Megan Kalata reached out to all 50 states and D.C. to determine if the reporting requirements identified below applied to multiple settlements. Juweek Adolphe created the interactive map. Our joint methodology may be found here.

“States’ Initial Promises to Publicly Report Their Opioid Settlement Expenditures” by Christine Minhee, OpioidSettlementTracker.com LLC, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to “remix, adapt, and build upon [the above] non-commercially,” provided that you credit me — “Christine Minhee, J.D., OpioidSettlementTracker.com” — and license whatever you produce using my work under identical terms. KFF also contributed, and information on their Creative Commons license can be found here. All rights reserved.

OPIOID SETTLEMENT TRANSPARENCY MAP

Loading...

This map was last updated March 30, 2023, with determinations based only on promises states made in writing as of February 24, 2023. It was created by Juweek Adolphe for KFF. It can be republished provided that it is credited to KFF Health News. More information on KFF’s Creative Commons license can be found here.

Initial research on public reporting requirements was done in collaboration with KFF Health News’ and published alongside a news article exposing issues arising from a lack of transparency on these funds. KFF’s Aneri Pattani, Colleen DeGuzman, and Megan Kalata reached out to all 50 states and D.C. to determine if the reporting requirements identified here applied to multiple settlements. Juweek Adolphe created the interactive map. Full methodology above and below.

"MOST SETTLEMENT AGREEMENTS DO NOT REQUIRE PUBLIC REPORTING OF OPIOID REMEDIATION EXPENDITURES"

OpioidSettlementTracker.com’s Global Settlement Tracker’s reported sum of settlements between opioid corporations, states, and localities has reached $54.45 billion… and counting.

The grand majority of this sum remains unattached to explicit requirements to publicly report opioid remediation expenditures.

Unless states add to their initial public reporting promises, we will be heading into a data desert: one where we will have far more information about the mistakes that got us here and their continued impact, and far too little data on the efficaciousness of these billions of settlement dollars.

The below summarizes the three biggest opioid settlements’ reporting requirements. States’ voluntary commitments to publicly report more than the below are collected on this page here.

$26 billion

distributors

McKesson, Amerisource-Bergen, and Cardinal Health

drugmaker

Johnson & Johnson

The Distributor and Janssen documents merely request that states self-report their non-opioid remediation spending — just 15% of funds — up to settlement administrators. BrownGreer will then report on this 15% slice to the public.

Status of settlement — finalized 2022, with most states in at least year 1 receipt of funds

Only 15% of these funds “must” be publicly reported. The Distributor and Janssen agreements speak to states’ obligations under our biggest joint opioid settlement. Section V.B.1 requires states to spend at least 85% of Distributor and 86.5% of Janssen payments on the broad definition of “opioid remediation,” which Section I.SS defines to include the programs and expenditures in Exhibit E, reimbursement for past opioid remediation expenditures, and “reasonabl[y] related” administrative expenses. Section V.D.1 further requires 70% of payments to be spent on future opioid remediation, ultimately leaving states with these spending restrictions:

70% must be spent on future opioid remediation (Sec. V.D.1)

15% on reimbursements for past opioid remediation expenditures (Sec. V.B.1)

15% on non-opioid remediation uses (Sec. V.B.2)

It is this unrestricted, non-opioid remediation slice that is subject to the Distributor and Janssen documents’ only public reporting requirements!

See BrownGreer’s Non-Opioid Remediation Use Reporting

For those who are curious: States and localities must merely volunteer to self-report any uses of settlement funds for non-opioid remediation purposes to settlement administrators…

Section V.B.2 (see also Exhibit L Section V.A.i): “While disfavored by the Parties, a Settling State or … Subdivision … may use monies from the Settlement Fund (that have not been restricted by this Agreement solely to future Opioid Remediation) for purposes that do not qualify as Opioid Remediation. … [S]uch Settling State or … Subdivision … shall identify such amounts and report to the Settlement Fund Administrator and …Distributors how such funds were used[.]”

Importantly: “It is the intent of the Parties that the reporting under this [section] shall be available to the public,” but not required.

Exhibit L Section V.A.i: “The Directing Administrator will not require Settling States and Participating Subdivisions without any such uses of money to submit a report, and the Directing Administrator may treat the failure to submit a report as confirmation that a Settling State or Participating Subdivision had no such uses of money.”

This means: States’ failures to self-report will be interpreted as evidence of successful spend. What?

…and for the reports that are submitted, “Directing Administrator [BrownGreer] shall establish a process by December 31, 2022 to make th[is] reporting ... available to the public.” Exhibit L Section V.A.iii. See BrownGreer’s Non-Opioid Remediation Use Reporting.

Directing Administrator: “The institution or individual that fulfills the remaining obligations of the Settlement Fund Administrator, other than those performed by the Directed Trustee.” Exhibit L Section I.C.

Directed Trustee: “The banking institution where the Settlement Fund is established and which distributes the funds according to the instructions of the Directing Administrator.” Exhibit L Section I.B.

About that Directed Trustee… “Pursuant to the Letter Agreement dated February 25, 2022, Wilmington Trust, N.A. was selected as the Directed Trustee.” Ex.L-1 footnote 17.

Pray tell: Is the same Wilmington Trust whose executives settled with the SEC for its 2008 federal bank bailout malfeasance? See, e.g.,

"Statement of U.S. Attorney David C. Weiss Regarding Wilmington Trust Company"(Dept. of Justice, 7/6/2021)

"U.S. drops financial crisis-era prosecution of four Wilmington Trust executives" (Reuters, 7/6/2021)

"Ex-Wilmington Trust president reaches settlement with SEC" (AP, 11/1/2022)

The CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart documents merely request that states self-report their non-opioid remediation spending — just 4.5%, 5%, and 15% of funds, respectively — up to settlement administrators. Whether these amounts will be reported to the public remains to be seen.

PEC’s “Key Dates.” For more, visit nationalopioidsettlement.com.

Status of settlement — not yet finalized, disbursement more or less a matter of when

state sign-on process complete Dec. 2022, subdivisions remain

see right (click to expand)

The CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart agreements speak to states’ obligations under our second biggest opioid settlement. Like the Distributor and Janssen agreements above, Walmart’s Section V.B.1 requires no less than 85% of payments to be spent on the broad definition of “opioid remediation.” (CVS and Walgreens go further; their Section V.B.1 require 95.5% and 95% opioid remediation thresholds, respectively.) Section V.D.1 of all three pharmacies’ agreements similarly requires 70% of payments to be spent on future opioid remediation.

Section V.B.2 of the Distributor, Janssen, CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart settlement agreements are virtually identical, which means that states are encouraged to self-report only non-opioid remediation spending (which CVS caps at 4.5%, Walgreens at 5%, and Walmart at 15%). However, the pharmacies’ Exhibit L — the “Settlement Fund Administrator Terms” that will determine whether these amounts will be publicly reported by settlement administrators (example here) — is “to be inserted prior to the Threshold Subdivision Participation Date,” which Section II.B.1 states is March 31, 2023 “or such later date as agreed to in writing” (i.e., April 18, 2023, as the PEC provides here).

CVS’s Section V.B.2 adds this sentence: “Such expenditures shall be reported to the Settlement Fund Administrator and CVS by January 31 of the year following the calendar year in which they are made.”

Allocations of all NOAT Funds (state/local abatement monies) must be reported UP and OUT.

Status of settlement — may not even get finalized, disbursement matter of if

if Purdue loses its federal appeal (i.e., if the Second Circuit Court of Appeals declines to reverse rejection of Purdue’s bankruptcy plan’s approval [whew]) → drawing board

if Purdue wins → still needs a federal bankruptcy court’s (re)approval

in either case, Supreme Court appeal possible

The National Opioid Abatement Trust Distribution Procedures (NOAT TDP) “establish the mechanisms for the distribution and allocation of funds … to the States and Local Governments.” NOAT TDP Sec. 7.1 requires states to publicly report their NOAT Fund expenditures:

“At least annually, each State shall publish on its lead agency’s website and/or on its Attorney General’s website … a report detailing for the preceding time period, respectively (i) the amount of NOAT Funds received, (ii) the allocation awards approved … , and (iii) the amounts disbursed on approved allocations, to Qualifying Local Governments for Local Government Block Grants and Approved Administrative Expenses.”

*as of 3/30/2023, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals has yet to rule on this case

PUBLIC REPORTING Q&A

A bit o’ background as to why the above analysis was necessary at all.

Jump to:

Your analysis shows that many states have some type of intra-state reporting requirement, but not as many have public reporting requirements. Why do you think that is? →

What could be done to improve public transparency on how this money is used? →

Would it be a big bureaucratic or administrative lift for states to require more public reporting? →

How do you hope this analysis will be used? In an ideal world, what outcome would result? →

Your analysis shows that many states have some type of intra-state reporting requirement, but not as many have public reporting requirements. Why do you think that is?

Because they aren’t required! In at least a few cases, the cynic’s rationale is unfortunately persuasive: If states can receive their settlement monies without having to subject themselves to extra legwork and scrutiny, why would they?

States do have to fess up when their opioid settlements under the $26 billion “big three” distributors/J&J deal and the $13 billion “big three” pharmacies are spent on things wholly unrelated to our overdose crisis. But these “non-opioid remediation expenditures” are capped at just 15% of a state’s total spending, which means that these agreements also do not require states to report any of their spending to the public themselves… let alone track exactly how the biggest 85% chunk was spent on opioid remediation.

So, the states with robust requirements to report opioid remediation expenditures somewhere are doing a bit more than the least, but still aren’t doing the most. Our country’s spending failures with the big tobacco master settlement agreement loom large. Requiring a certain threshold of abatement spending is the settlement agreements’ bare minimum attempt at avoiding a repeat of our big tobacco spending nightmares. But will the bare minimum help us move forward? There are opportunities to heal some old drug war wounds. But it’ll come only from states working through some of their big tobacco settlement spending shame by doing the state budgetary version of a vulnerability practice (volunteering to publicly report all of their opioid settlement expenditures).

What could be done to improve public transparency on how this money is used?

The lowest-hanging fruit in my view are those states who could be publicly reporting nearly all of their settlement spending, if they only chose to make public all of the opioid remediation expenditure reports they’re collecting someplace in some intrastate fashion.

Some states seem to believe that heavy intrastate reporting of opioid remediation expenditures provides sufficient due diligence. If a state’s opioid remediation expenditures are then collected and collated and sent by some entity to the AG, the legislature, and the governor, it’d even be reasonable to assume that they may at some point will become publicly accessible.

But this is a far cry from what we want. The difference between publicly accessible and publicly reported is absolutely one of equity.

With the privilege of my law degree, I’m able to dig up more evidence of spend than someone limited to Googling for that information. I want state and local decisionmakers to similarly recognize the inherent privileges undergirding the process of opioid settlement spend — the biggest one being that their billions wouldn’t be possible without hundreds of thousands of individuals dying first — and speak their opioid settlement expenditures loudly and clearly into the mic for the people at the back of the room to hear.

Would it be a big bureaucratic/administrative lift for states to require more public reporting?

For the states whose settlement spending plans require that opioid remediation expenditures be reported somewhere in an intrastate fashion, I think not! If all of that information is compiled but it isn’t being reported out to the public, what gives?

Anecdotally speaking, I have observed states with preexisting partnerships with research universities or data-loving departments of health fare better in the public expenditure reporting game. I’d imagine the task of creating an opioid settlement spending dashboard (or the like) would be easier for groups who’ve already gone through the (technical and often political) hurdles involved in the creation of overdose data reporting tech.

What do you hope comes from this analysis you’ve done? How do you hope it’s used? And in an ideal world, what outcome would result?

At the moment, whether we will know which specific interventions were funded by settlement dollars, whether they were generally carcerally or harm reduction modality-oriented, or whether they even reduced overdose deaths at all will be a state-by-state question.

This analysis is my attempt to show people what I see: that we are actively marching into a data desert… one where we will have a lot more information about how we got here and the continued impact of the crisis than we will about how these billions of dollars of opioid settlement winnings are being spent.

But it’s all inherently a hopeful exercise because I’m entirely convinced that states can peer pressure themselves into making it rain. This analysis documents and calls attention to this intemperate landscape. States have been heads-down with their own opioid settlement processes for quite a while; this is their opportunity to peep out of their silos to look at the public reporting promises other states have made. I have hope that if they merely knew how well states like Colorado and New Jersey were doing, they’d strive to compete.

Initial Investigation Methodology

Re: States’ Initial Promises to Publicly Report Their Opioid Settlement Expenditures (above). Original KFF Health News coverage here.

Christine Minhee, founder of OpioidSettlementTracker.com, analyzed each state’s plan for handling opioid settlement funds, along with relevant laws, executive orders, and public statements, to identify requirements to report how the money is spent. She is sharing her analysis first with KFF.

Although some governments may opt to be more transparent than required, Minhee’s determinations were based only on promises they had made in writing as of Feb. 24, 2023.

For a state to be classified as publicly reporting 100% of its funds, it needed to meet the following criteria:

Reporting requirements are specific about both where the money is going and what it is for. For instance, saying $1 million went to the health department wouldn’t qualify, but saying $1 million went to the health department to buy naloxone for first responders would. Requirements that mention audits or monitoring compliance without mandating listing of specific expenditures would not meet the standard.

Reporting requirements apply to all settlement funds, including those controlled by state agencies, local governments, and councils overseeing abatement funds.

Requirements pass the “Googleability test”: Could a typical person reasonably find their state’s opioid settlement expenditures by searching online? If people must file public records requests or weed through a 100-page budget document for the information, that state would fall short.

If a reporting requirement did not pass the “Googleability test” but stipulated that, for example, local governments report their expenditures to the legislature or that the state health department report its expenditures to the attorney general, it could instead be classified as going to an oversight body. Although these reports may eventually surface, they were not counted as public because there was no explicit requirement for them to be made accessible to the average person.

The documents Minhee analyzed originated primarily from states’ planning for settlements with “the distributors” — AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson — and drugmaker Johnson & Johnson, which were the first national opioid settlements to be finalized. Several other settlements have yet to be finalized, including with Purdue Pharma. KFF’s Aneri Pattani, Colleen DeGuzman, and Megan Kalata reached out to all 50 states and Washington, D.C., to determine if the reporting requirements identified in their documents would apply to settlements with all companies or just the distributors and Johnson & Johnson. Four states did not answer the question: Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. KFF’s determinations for them derive from how widely or narrowly they defined “settlement” in their public documents.

Information on the finalized dollar amounts from the distributor and Johnson & Johnson settlements, as well as who controls the money in each state, comes from attorney general press releases and public statements compiled by Minhee.

Information about which settlements each state is participating in comes from National Opioids Settlement, a website run by the Plaintiffs’ Executive Committee involved in opioid litigation.

The information presented is expected to change as states pass new laws and enter into new settlements.